Chapter 4

Responsible science

Responsible science is characterised by its commitment to ethical and sustainable research. It emphasises active engagement with the public and independence from external influences. This chapter starts by looking at the perceived independence of science, particularly in terms of how it is governed and funded. It then covers the actions of scientists and regulators, and how effectively they are seen to communicate with the public. Finally, it looks at the perceived interactions between science, the government and policymaking.

Chapter 4

Responsible science

Responsible science is characterised by its commitment to ethical and sustainable research. It emphasises active engagement with the public and independence from external influences. This chapter starts by looking at the perceived independence of science, particularly in terms of how it is governed and funded. It then covers the actions of scientists and regulators, and how effectively they are seen to communicate with the public. Finally, it looks at the perceived interactions between science, the government and policymaking.

The overall story

This latest survey reinforces many messages around responsible science from previous years. There was broad support for scientists and those that regulate them to communicate more with the public. And clear majorities still felt the government should act in accordance with public concerns around science and technology, and that experts should play an important role in advising the government on scientific developments.

However, people remained worried about the independence of scientists being eroded by funders, government and industry. Moreover, they appeared less willing than in 2019 to place their trust in those governing and regulating science and wanted scientists and the public to have a greater hand in regulation. A potential explanatory factor behind these attitudes is the public’s understanding of science funding and regulation.

The government and private companies were viewed as the top funders of scientific research. And more people thought that funders, government ministers and private companies were in charge of setting the rules and regulations for scientists, than thought that these groups should be in charge. In other words, people were predisposed to think that government and industry had power and influence over scientists.

Nevertheless, fewer people were raising concerns around a lack of independence and communication in 2025 than before. This may be driven by the differences between younger and older generations. Compared to the average, young adults aged 16 to 24 tended to place less importance on the independence of scientists, were more likely to disagree that scientists should discuss the social and ethical implications of their work, were less likely to say that those who regulate science should communicate with the public and were more neutral about experts advising the government on science issues.

Headlines

4.1 The perceived independence of scientists

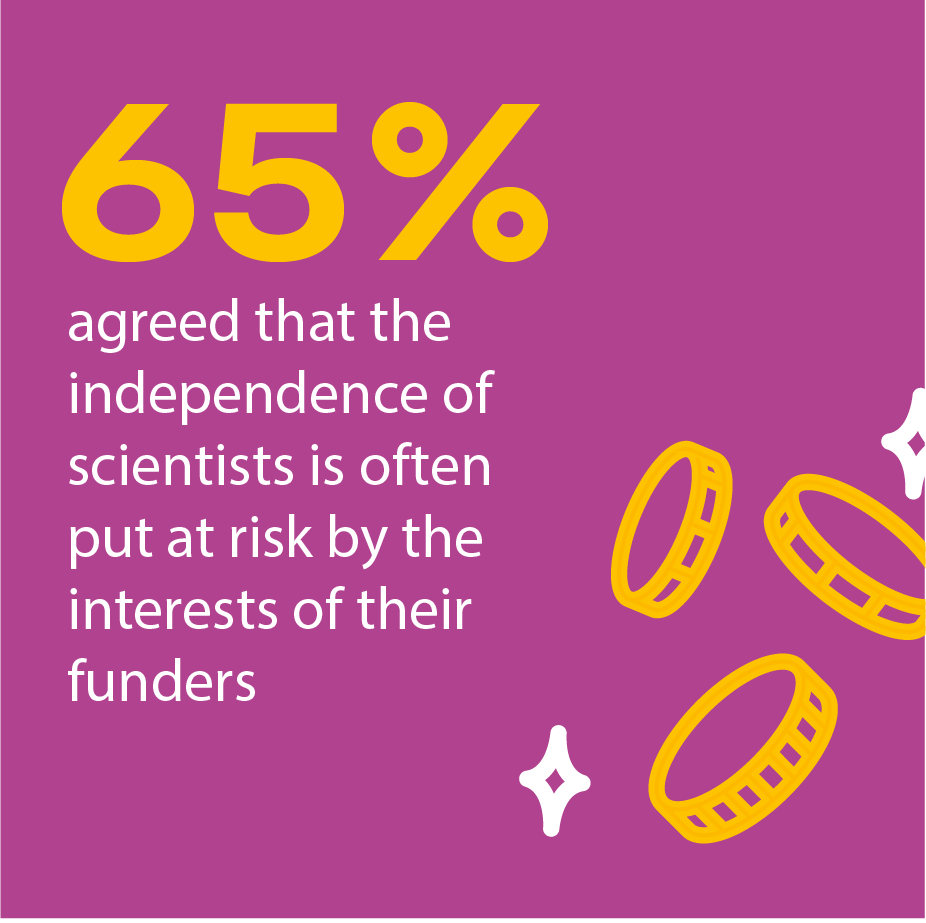

Two questions in the survey highlight how strongly the public valued and were concerned about scientific independence. Eight in ten (82%) agreed it is important to have some scientists who are not linked to business. Furthermore, around two-thirds (65%) agreed that the independence of scientists is often put at risk by the interests of their funders. Those who felt informed about science were more likely than average to agree with both sentiments.

This remained an important issue for the public, although it is worth noting that concern about scientific independence being compromised by funders has dropped to its lowest level since the question was first asked (in 2005). This is shown in the chart below.

The public valued scientific independence but were concerned about it being put at risk.

4.2 Funding science

Growing the economy

The private sector is the largest funder of scientific research in the UK. Evidence of this comes from Office for National Statistics data looking at research and development spending, which shows that the largest funder is the private sector followed by the higher education sector, then government directly, then charities.

PAS has historically found that people overestimate the level of government funding of scientific research in the UK. This year’s study is no exception, although the questions asked this year are not directly comparable to previous years.

The prompted list of responses to the question of who funds scientific research in the UK is shown in the chart below. The top response by far was government. The chart also highlights the relatively basic awareness and understanding that the public had about the role of publicly funded institutions such as the Research Councils (included on the prompted list, but without a further explanation for those completing the survey). It also shows that other jurisdictions, such as the EU and other countries, were more rarely felt to play a role in UK scientific research.

4.3 Rules and regulations

The perceived power held by those setting the rules and regulations around science is encapsulated in a longstanding question, dating back to 2005, shown in the chart below.

In 2025, just over two-fifths (43%) agreed that people have no option but to trust those governing science, while a quarter (25%) disagreed. This has declined since its peak in 2014. This is a complex statement to disentangle, but the shift may suggest that the public has become less willing to take science governance and regulation for granted.

The public may have become less willing to take science governance and regulation for granted.

The following chart shows who the public currently thought set the rules and regulations for scientists to follow, as well as who they thought should be doing so. This highlights the major role that many felt that global institutions played, and ought to play, in regulating scientists. It also illustrates public concerns around the perceived influence of government ministers, private companies and the funders of scientific research.

As noted in the previous section, the funding of scientific research in the UK was most commonly attributed to the government and to private companies.

Moreover, Chapter 2 reported that scientists working for private companies and for government were the least trusted group of scientists.

At the same time, the chart below shows that more people wanted scientists themselves and the public to have a hand in regulation, than felt were currently involved.

While similar questions were asked in previous years, these were unprompted (which was not possible this time due to the PAS survey moving online and being asked on a screen). As such, this data is not directly comparable with previous years.

Three small but significant subgroup differences emerged at these questions:

Those with high science capital, i.e., those who interacted more with science and scientists as part of their daily lives, were more likely than average to say that scientists themselves should be involved in setting the rules and regulations.

There was a contrast between under-55s and those aged 55 or higher – the former were more likely to want the public to be involved in setting rules and regulations.

People from Asian ethnic backgrounds were also more likely than average to want the public to be involved.

4.4 Communicating with the public

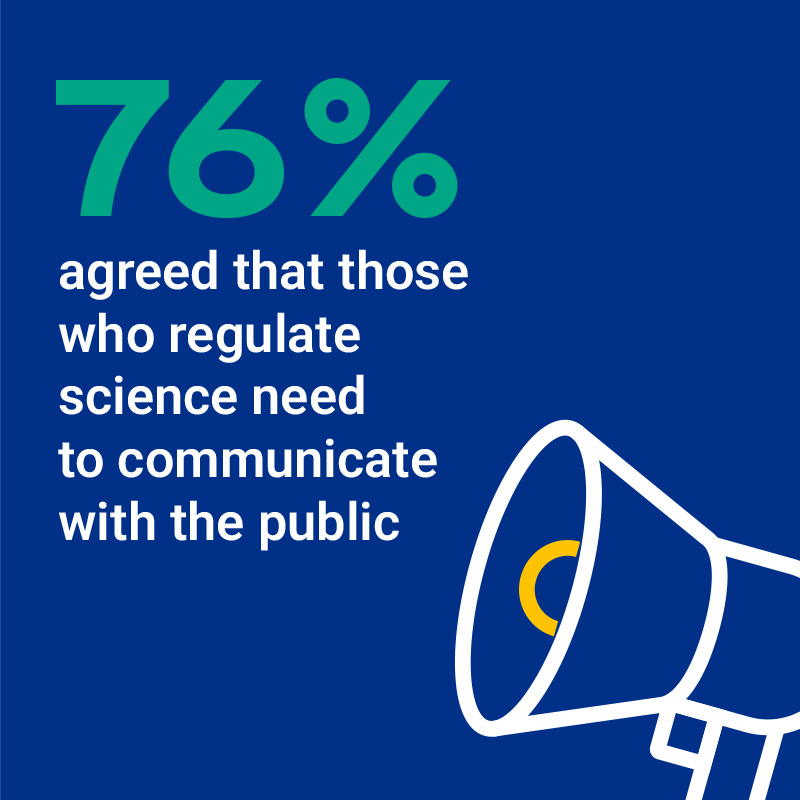

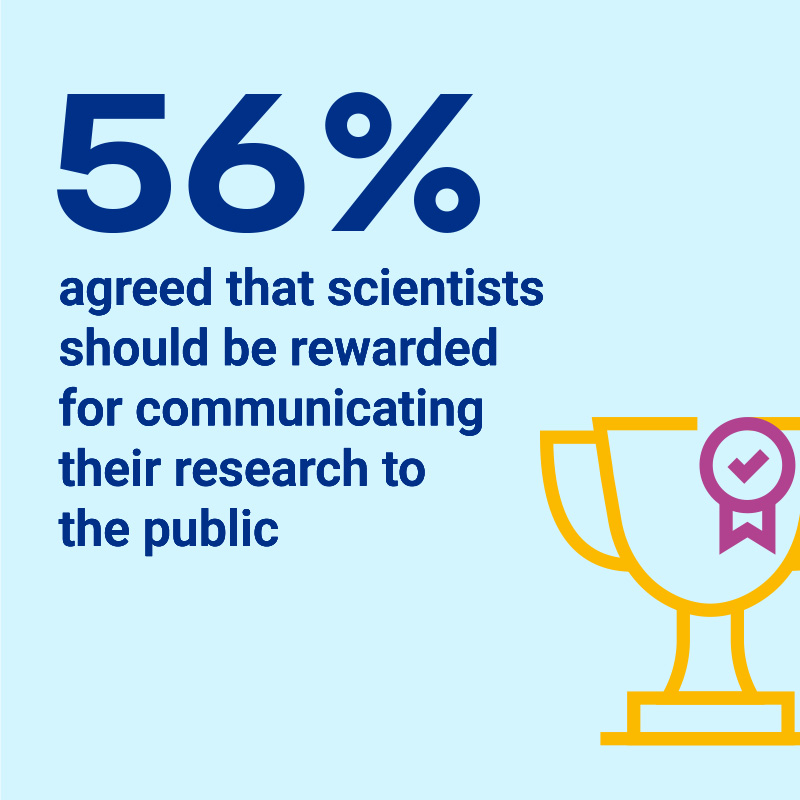

A majority of the public wanted regulators and scientists to be communicating with the public. There was also majority agreement, albeit to a lesser extent, that scientists should be rewarded for this kind of science communication work.

76%

agreed that those who regulate science need to communicate with the public. This sentiment was, however, less strong among young people aged 16 to 24 (63% agreed).

59%

agreed that they would like more scientists to spend more time discussing the social and ethical implications of their research with the public – a statement that resonated similarly across genders and age groups.

56%

agreed that scientists should be rewarded for communicating their research to the public.

Those with high science capital – who had more regular interaction with science and scientists in their daily lives – were more supportive of communication from scientists and regulators, and of rewarding those who communicate their research.

The above sentiments reflected a majority of the public. However, the proportions that wanted regulators to communicate with the public, and scientists to spend more time discussing social and ethical implications, have both fallen since 2019, as shown in the following chart. This was not because more people disagreed with these statements in 2025. Instead it reflects an increase in the proportion who neither agreed nor disagreed.

These findings contrast with Chapter 2, where we reported that ethical conduct was a driver of trust. The rising ambivalence towards science communication in this latest survey (i.e., increasing proportions neither agreeing nor disagreeing) highlights the considerable challenge that scientists and regulators face in influencing trust.

4.5 Science in government

and policymaking

Several questions reflected people’s wishes for public concerns about science to be reflected in policymaking and a desire for the government to involve the relevant experts to shape science policy. However, there was a great deal of uncertainty around whether and how this might be happening already.

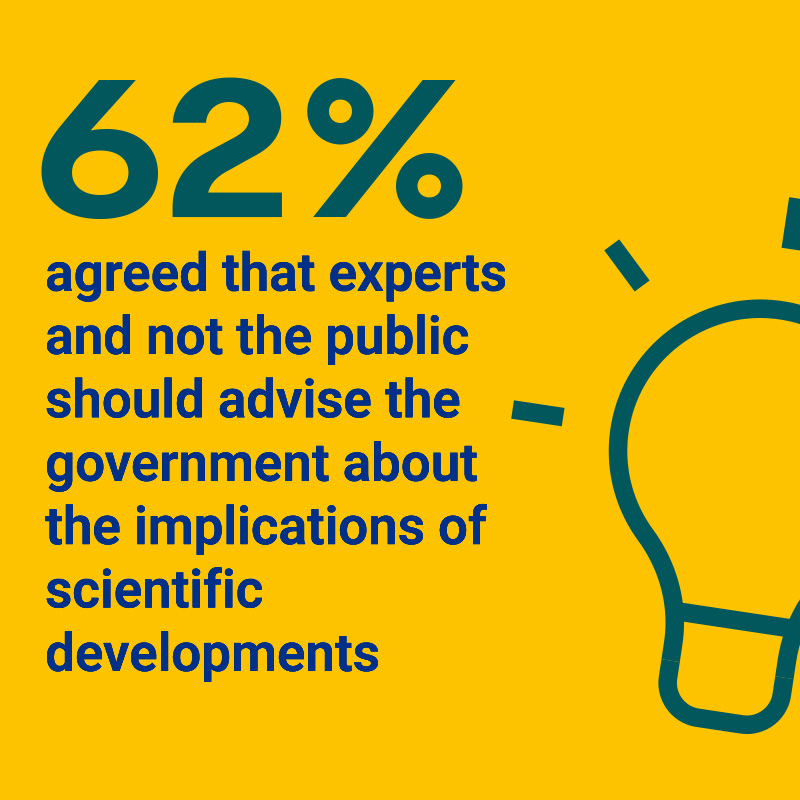

62%

agreed that the government should act in accordance with public concerns about science (a broad statement, not attributable to any single science topic or policy area).

62%

also agreed that experts, not the public, should advise the government about the implications of scientific developments. Young people aged 16 to 24 were less likely to agree (54%).

25%

agreed that government ministers regularly use science to inform decision-making, whereas 28% disagreed, and the biggest proportion (43%) neither agreed nor disagreed – this was a new question for 2025.

The majority felt that the government should act in accordance with public concerns about science. However, this sentiment has waned since 2019, dipping even more sharply from its peak in 2005, as illustrated in the chart below. There were more people neither agreeing nor disagreeing than before, which follows a broader pattern seen across questions.

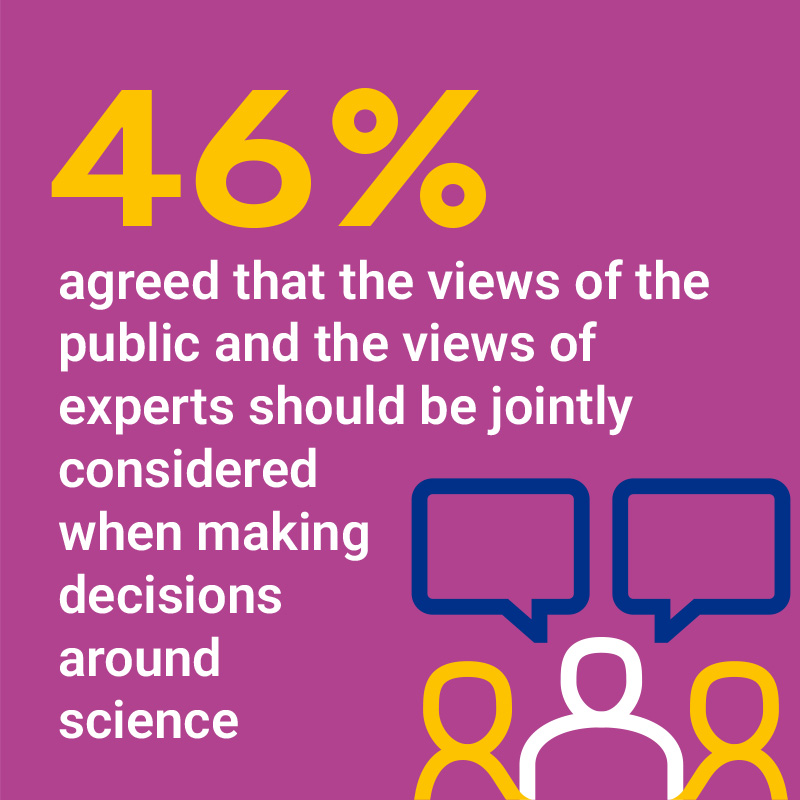

A new question was added in 2025 to explore whether the views of the public and the views of experts should be jointly considered when making decisions around science. Just under half (46%) agreed with this approach. However, a sizeable minority (21%) disagreed, highlighting the more contentious nature of experts and the public getting an equal say. Young people aged 16 to 24 were more likely to disagree than older people aged 65 and above (26% versus 15%). Those with high science capital – more connected to science and scientists through their everyday lives – were also more likely than average to disagree (34%, compared to 21% overall).