Chapter 6

People participate in science as a subject at school, in science careers, and through activities like consultation, dialogue or citizen science. This chapter first explores people’s perceptions of science at school, followed by careers in both science and in research and innovation roles. It subsequently looks at public perceptions of and appetite for wider forms of involvement.

Secondly, the chapter covers perceptions of representation, equality and diversity in science. This was measured with a largely new set of questions for 2025.

Chapter 6

People participate in science as a subject at school, in science careers, and through activities like consultation, dialogue or citizen science. This chapter first explores people’s perceptions of science at school, followed by careers in both science and in research and innovation roles. It subsequently looks at public perceptions of and appetite for wider forms of involvement.

Secondly, the chapter covers perceptions of representation, equality and diversity in science. This was measured with a largely new set of questions for 2025.

The overall story

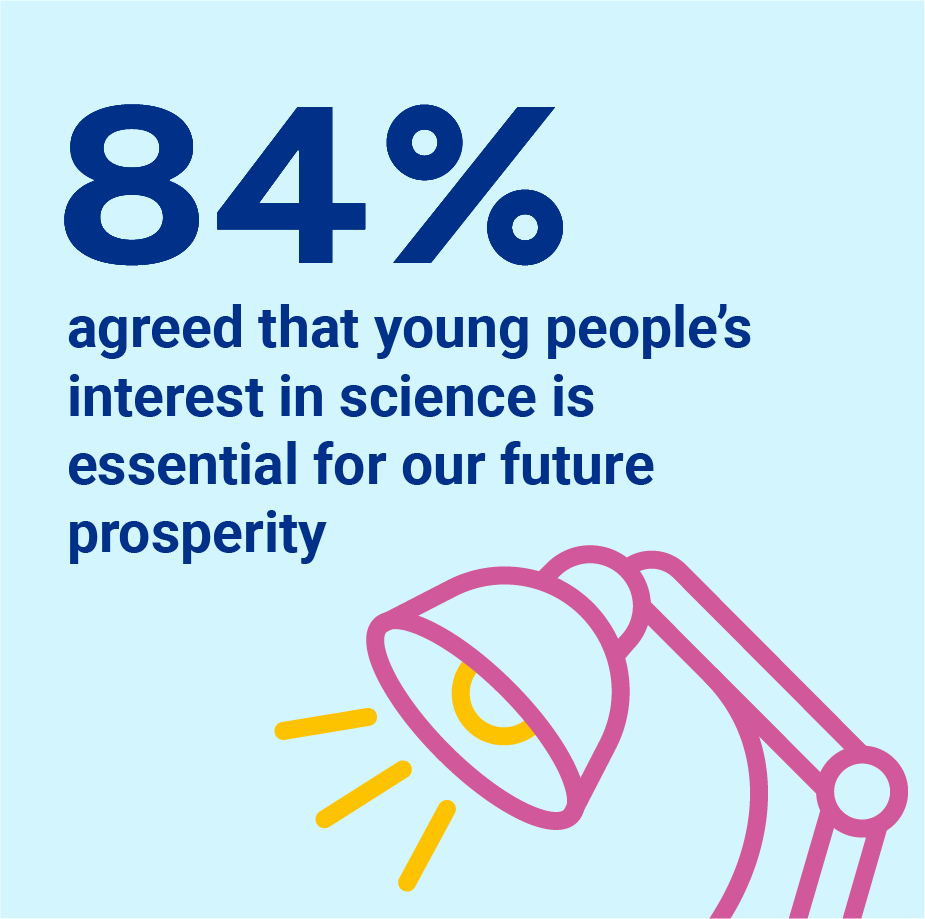

PAS once again highlights the challenges around public participation in science. On one hand, increasing public participation was of great importance to people, in terms of careers, and involvement in decisions and policy on science issues. The vast majority felt that young people’s interest in science is essential for our future prosperity, that people should have more say in decisions about science, and that they personally were clever enough to understand science and technology – the latter opinion had risen consistently since 2000. Most people also believed that science needs to be representative, in terms of who carries out scientific studies, who takes part in them, and who benefits from them.

On the other hand, as in previous years, people were often more interested in knowing the public was involved, rather than getting involved themselves. And there was relatively low willingness or confidence to get involved in ways that could be time consuming or require more specific expertise.

Moreover, several trends pointed to increasing uncertainty or ambivalence compared to previous years, particularly among young people aged 16 to 24. For example, they were the most likely age group to agree that school put them off science.

At the same time, expectations were high, with most thinking that the government was doing too little to consult people on science. There were also polarised views about science benefiting the rich more than the poor, especially among those currently facing financial hardship, and about a perceived lack of equal opportunities to pursue a career in science.

Headlines

It was a widespread view that young people’s interest in science is essential for our future prosperity. A total of 84% agreed and just 4% disagreed with this sentiment. This was in line with previous years, back to when the question was first asked in 2008.

In this context, it is important to understand perceptions of science in school, and how this carries forward into people’s adult lives. PAS has regularly asked two questions about this, which both suggest that views have remained broadly positive on this topic:

%

agreed that school put them off science. This was a minority view, with double this proportion disagreeing (52%).

%

agreed that the science they learnt at school had been useful in their everyday lives (versus 31% that disagreed), although this was a more polarising statement.

A new question this year provides an alternative viewpoint, more positive than in the second point above. Half (49%) agreed that studying science subjects (e.g., physics, chemistry or biology) at school or beyond had given them the skills to think critically in their daily lives. A fifth (22%) disagreed. This suggests that people can often have a more nuanced view on the usefulness of school science in their daily lives. At this question, people from Black and Asian ethnic backgrounds were more likely to agree (65% and 60% respectively).

However, positivity about school science has declined. In 2019, 59% disagreed that school put them off science (i.e., they had a positive view). In 2025, just 52% disagreed. Instead, more people neither agreed nor disagreed. Responses to this question had previously been stable since it was first asked in 2005.

Similarly concerning was the split by age at this question. Young people aged 16 to 24 were more likely than average to agree that school put them off science (32% agreed, versus 23% overall). This could be because this age group completed their secondary education more recently, and therefore simply recalled it more vividly than older age groups. However, the two previous waves (2019 and 2014) did not find this difference between younger and older age groups – i.e., earlier generations of young people were more positive than the current generation.

Young people aged 16 to 24 were more likely than average to agree that school put them off science.

There was majority agreement that jobs in science were interesting, but fewer agreed these jobs were well-paid. As the following chart shows, opinions have become less positive on both counts since 2019 and compared to when first asked in 2011.

For the first time, parallel questions were asked about jobs in “research and innovation”. These received very similar answers to science, with 63% agreeing that jobs in research and innovation were very interesting, and 35% agreeing that working in research and innovation offers a well-paid career.

These questions also highlighted some important subgroup differences. The findings are shown for science below, but similar differences were also present for research and innovation:

Majority agreed that jobs in science were interesting, but fewer agreed these jobs were well-paid.

Young people aged 16 to 24 were more likely than average to disagree that jobs in science were interesting (13%, compared with 5% overall).

Those with a science or engineering degree were also more likely than average to disagree that science offered a well-paid career (30%, versus 13% overall).

The importance of consultation and dialogue

As previously covered in Chapter 4, a clear majority wanted public views to be reflected in science policy, with 62% agreeing that the government should act in accordance with public concerns about science. Other data from the survey suggests this was not perceived to be happening enough, with just 12% agreeing that the public is sufficiently involved in decisions about science and technology.

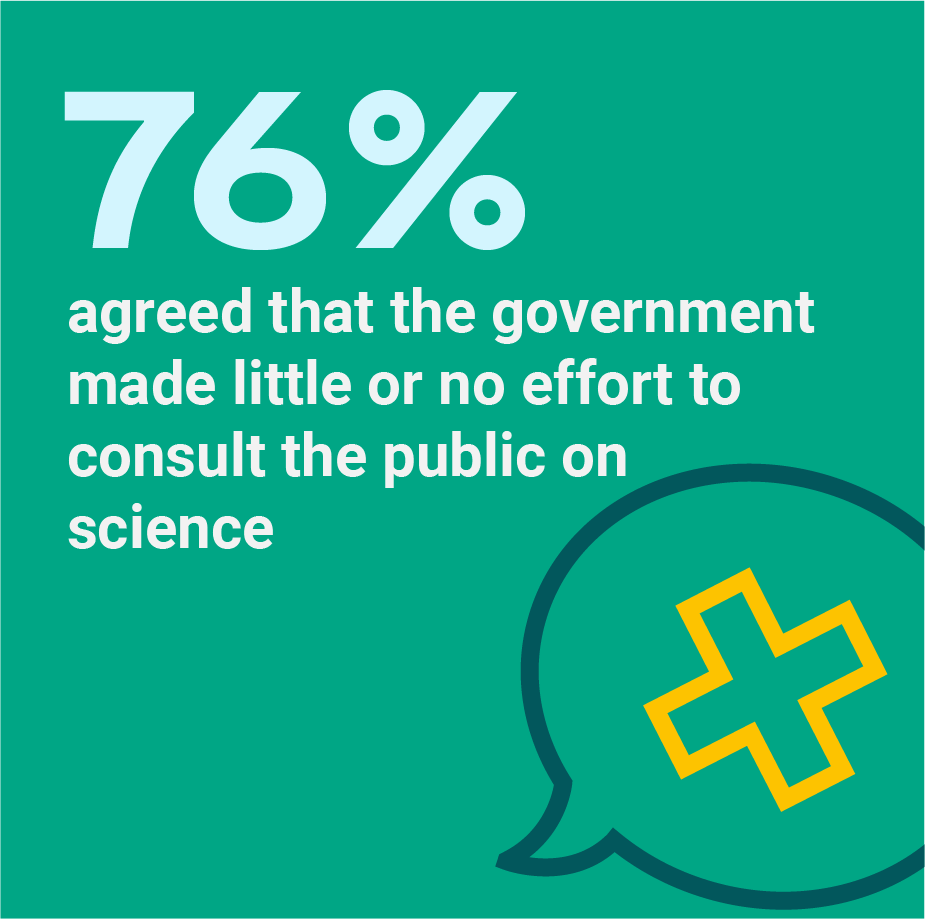

The public largely placed responsibility for this on the government, with 76% saying the government was not making very much effort, or no effort at all, to consult the public on science. A fifth (19%) felt they were making a fair amount of effort, and 2% said they were making a great deal of effort.

On a related note, the idea that scientists should listen more to what ordinary people think was also popular. However, the findings suggest that less emphasis was placed on scientists themselves than on government to consult. Around half (50%) agreed with this viewpoint while 14% disagreed, and a third (35%) neither agreed nor disagreed.

Similarly critical views on efforts to involve the public have been raised in previous years of PAS. However, as the chart below shows, people have become more critical of government in relation to consultation on science, and less so of scientists themselves.

People have become more critical of government in relation to consultation on science, and less so of scientists themselves.

There were notable subgroup differences by gender and age:

Women were more likely than men to want more involvement from the public in decision-making, and for scientists to listen more to “ordinary people”. In contrast, men were more likely than women to think the government was already doing enough to consult the public and had less desire for ordinary people to get more involved.

16 to 24 year-olds were more likely than average to think the government was making at least a fair amount of effort to consult the public on science (30%, versus 21% overall).

Getting personally involved in decisions about science

A common challenge for policymakers, given people’s desire for more consultation and public involvement in decision-making, is that a majority of the public are not especially willing to get involved personally. This is reflected in the following chart. The findings for “science” were close to the 2019 and 2014 results (when the question was introduced). The parallel question asking about “research and innovation” was new for 2025 and received a very similar set of responses.

These responses are not unique to decision-making on science, research and innovation. The earlier Audit of Political Engagement research series, which ran until 2019 in the UK, regularly highlighted a lack of willingness among individuals to be personally involved in local and national decision-making on broader political and governmental issues.

The responses varied by gender, with men showing a greater desire than women to have more of a say in science, and in research and innovation issues. Women instead were more likely than men to want to know that the public was being involved, but fewer wanted to be involved personally.

How would people want to get involved?

The previous section highlighted a lack of willingness to get involved personally in science, but this may reflect a lack of awareness of the range of ways in which people can get involved. To that end, a new question was introduced in 2025 to explore various types of science-related activities the public might want to be involved in. The list, shown in the chart below, suggests there was relatively widespread interest in certain forms of participation such as taking part in research studies or volunteering.

There was less interest in activities that could be more time consuming or require more specific expertise, such as taking part in public discussions and debates, or helping organise festivals, talks or events. It is also a possibility from these findings that events and opportunities tied to people’s local areas would have a stronger pull than other forms of engagement.

There were notable differences between genders. Women showed more of an interest than men in volunteering roles, while men gravitated more towards roles that involved them in shaping science policy.

Younger groups aged 16 to 24 were also more likely than average to express interest in all the activities listed. People from Asian and Black ethnic groups were also more likely than White people to express interest in participating in ethics committees.

The importance of representation in science

The 2025 survey introduced a new set of questions to explore people’s views on representation, equality and diversity within science. In particular, three new questions asked about the representation of diverse groups, referring specifically to “women, ethnic minorities, all social classes, disabled and neurodivergent people”.

As the chart below shows, a clear majority of people thought it was important to have representation in science, across all of these aspects. The statement saying that this would lead to better quality science garnered a more neutral response than the others, suggesting that people were perhaps more unsure how improving representation could improve quality.

A clear majority of people thought it was important to have representation in science.

Gender differences were evident here, with women more supportive of greater representation than men across all three of the statements above. In addition, those with high science capital (who had more interaction with science and scientists in their day-to-day lives) were more likely than average to disagree that scientists should be required to involve all groups of the population in their research, and that the people working in science should be representative of the population. These findings may benefit from further unpacking in future research.

Women are more supportive of greater representation than men.

Is science representative?

Opinions were divided as to whether science was succeeding at representing or delivering for all groups equally:

A third (34%) agreed that scientific advances tended to benefit the rich more than the poor, with a similar proportion disagreeing (31%), or neither agreeing nor disagreeing (34%). This varied by age, with younger people more likely to agree than those aged 65 or over. Notably, those who said elsewhere in the questionnaire that they were finding it difficult to get by on their present incomes were also more likely to agree.

A new question was added this year to understand whether people felt personally represented in scientific research. Nearly half (48%) neither agreed nor disagreed that scientists “consider people like me” when designing their research. While 26% felt they did, a similar proportion (23%) disagreed. Those from an Asian ethnic background, and those who were finding it difficult to get by on their present incomes, were both more inclined to feel that scientists did not consider people like them.

Barriers to participation

PAS has long asked (since 2000) whether people think they are clever enough to understand science and technology. The perception that people are not clever enough – the question is asked inversely – has fallen consistently over the last 25 years, as the following chart shows. Therefore, this does not appear to be a major barrier to participation.

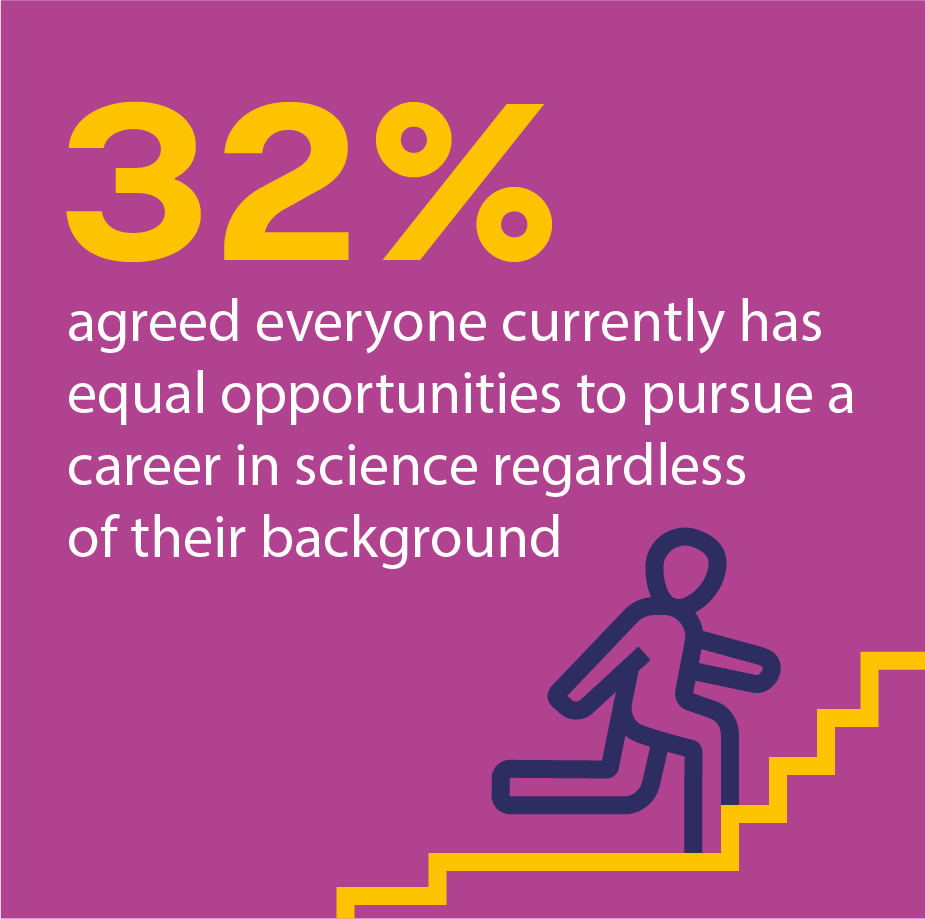

Opinions were considerably polarised as to whether everyone has equal opportunities to pursue a career in science.

Two new questions were included this year to further explore this theme. The chart below shows that while half would feel comfortable in places where science is discussed practised, a sizable minority (17%) would not. In addition, opinions were considerably polarised as to whether everyone has equal opportunities to pursue a career in science.

There were different responses by gender and age. Women expressed more scepticism than men that everyone has equal opportunities to pursue a career in science (45% versus 37% disagreeing). There was also greater disagreement among younger age groups (47% of 16 to 24 year-olds and 50% of 25 to 34 year-olds disagreed, versus 34% of those aged 65 or more).